opsys-sp24

Operating Systems Spring 2024

Project 6: Buffer / Cache

Objectives

In this project, you will build a buffer/cache, which is the central data structure used to manage I/O performance in an operating system. In this project you will apply many of the techniques and skills that you have learned over the course of the semester. You will:

- implement synchronized access to data structures from multiple threads.

- avoid deadlock between competing threads.

- improve the performance of the I/O system by managing memory effectively.

- schedule multiple pending operations in an efficient manner.

- develop even more expertise in C programming by using structures and pointers extensively.

This project may be done in pairs or singletons. Please submit your work to a single dropbox with a PARTNERS file that indicates the project members. Both partners will receive the same grade.

This is a challenging project that will take time to get right. Although the total quantity of code is not large (perhaps a few hundred lines) you will need to think carefully about data structures, thread synchronization, scheduling, and other issues. This will require extended time to think, troubleshoot, and think some more over the next few weeks. Get started right away!

Overview

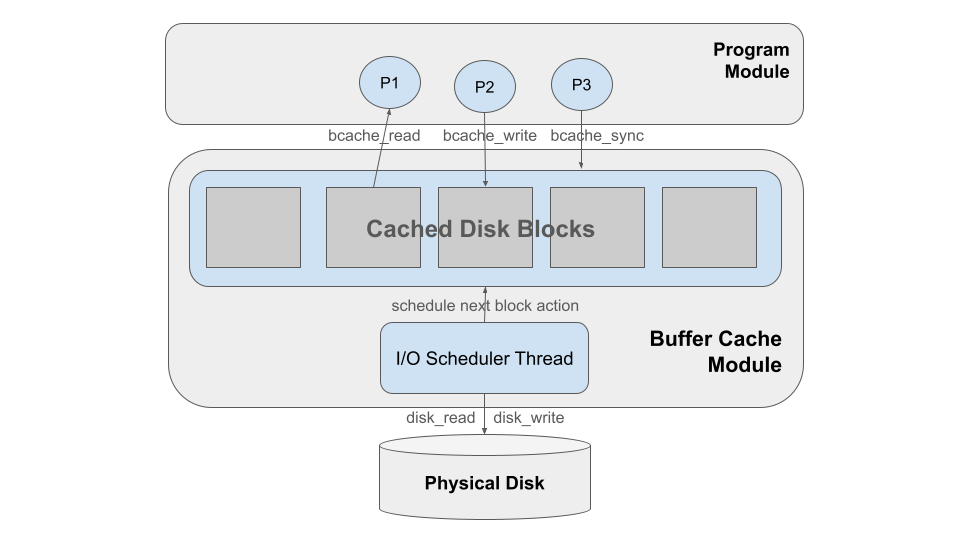

In this project, you will build a buffer/cache for an operating system. This will be a challenging but fun project which will help to reveal the inner workings of the OS, and shows the importance of managing memory as part of I/O performance. We will provide you with several programs that make disk requests, a simulated disk that satisfies those requests, and your job is to build the buffer/cache module that sits in the middle. This figure gives the overall idea:

At the top are a large number of programs running concurrently

and accessing the disk in different patterns:some sequentially,

some random, and some in concentrated areas. These programs

will make their requests known by calling the functions

bcache_read() and bcache_write(). (They also check what

they are reading to make sure it is correctly read back.)

When all the programs are

done, the main program will call bcache_sync() to finish up.

In the middle is the buffer/cache, the part that you will create.

This module implements the functions bcache_read, bcache_write,

and bcache_sync which both operate by manipulating the actual buffer data structure.

It consists of a number of 4KB blocks of memory, each representing

one block of data, in one of several states. The buffer/cache has

two combined jobs:

1 - It buffers blocks when they are written, so that the writing process may return quickly, and the data may be written to disk as time permits.

2 - It caches recently accessed data in memory, so that processes that return to the same data may access it at memory speed, instead of waiting for the dis.

Note that bcache_read and bcache_write should operate only on the

buffer data structure, they do not access the actual underlying disk.

That is the job of the I/O scheduler thread which runs in the background.

It considers the current state of the data structure, and performs

the actual disk_read and disk_write operations according to one of

several scheduling policies, updating the buffer structure as needed.

Finally at the bottom is the simulated disk, which is very similar to the one you used in the virtual memory project. It has the (simple) capabilities of a real disk, allowing you only to read and write one whole block at a time. Only one thread (the I/O scheduler) can access the disk at a time, and this is the performance bottleneck of the system. Each request to the disk will take at least 10ms, plus some extra time for the distance that the disk must travel since the last request.

Buffer / Cache Implementation

As in previous projects, the buffer/cache is at heart a data structure protected by a monitor (mutex and condition variables). Each block stored in the cache will consist of 4KB of the actual data, along with some additional values to indicate which block number it corresponds to on the disk, and the current state of the block.

Programs will access the buffer/cache using the following three operations:

int bcache_read( struct bcache *bc, int blocknum, char *data );

int bcache_write( struct bcache *bc, int blocknum, const char *data );

int bcache_sync struct bcache *bc );

As the name suggests, bcache_read should read a 4KB block from disk

into the buffer/cache, then copy the 4KB cached data into the data pointer

provided by the caller. bcache_write should copy 4KB from the data pointer

into the buffer/cache, and arrange for it to be written back to disk as time

permits. bcache_sync should pause until all pending writes in the buffer

have completed.

These three functions do not access the disk directly, but may modify

the state of the buffer cache, and may wait for the I/O scheduler

thread to take some action before returning.

The I/O scheduler thread running in the background does not interact

with the caller directly, but should examine the state of the buffer

cache, decide what action needs to be taken on a particular block,

and then perform disk_read or disk_write as needed to carry

out the action.

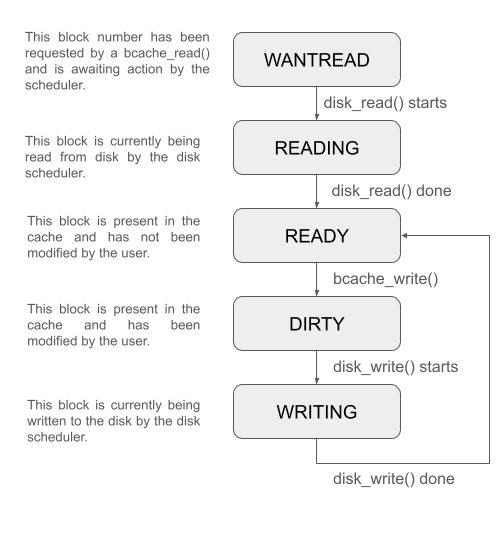

You will need to record the current state of each block in the cache, and we suggest that you use the following state machine:

WANTREAD

indicates a block that has been requested by bcache_read and is not

yet fulfilled. READING indicates a block that is currently being

read in by the I/O scheduler thread. READY indicates a block that

has been read into the buffer/cache and is ready to be used immediately.

DIRTY indicates a block that has been modified by bcache_write.

WRITING indicates a block that is currently being written to disk

by the I/O scheduler thread. Once a block has been written, it is now

clean and goes back to the READY state.

Example Operation

Here is an example of a few operations on the buffer/cache to give the idea.

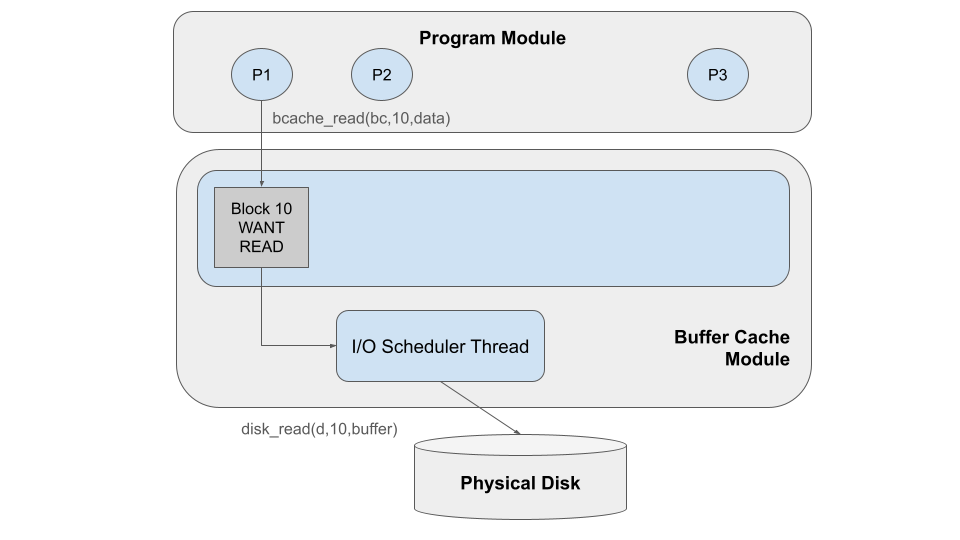

Suppose that we start with a completely empty buffer.

Process P1 acts first, issuing a bcache_read on block 10.

Because that block is not (yet) in the cache, the buffer cache reacts

by creating a new block in memory in the WANTREAD state. bcache_read then

waits for the I/O scheduler thread to take action. The scheduler thread

notices the waiting block, and takes action by changing it to the READING

state, and issues the disk_read operation, which may take some time.

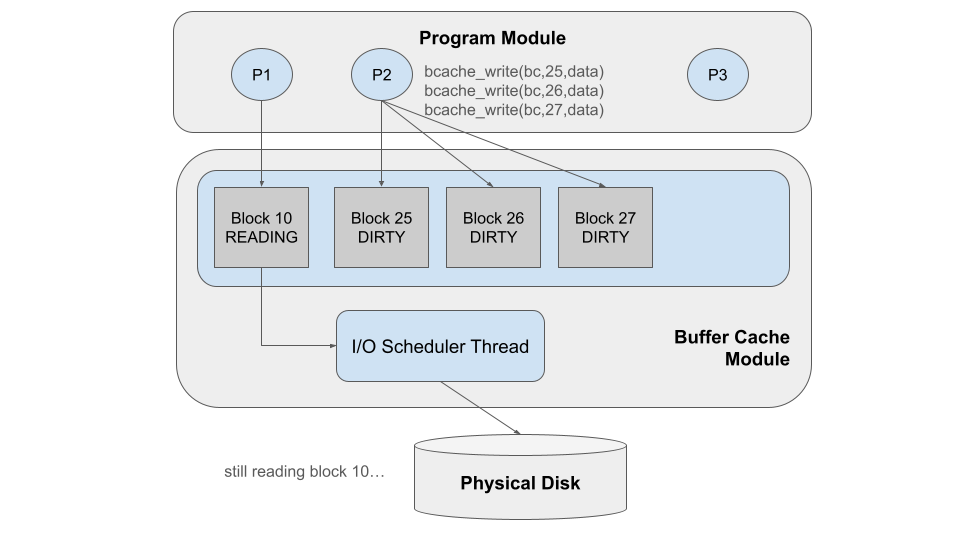

While the I/O scheduler thread is busy reading (and P1 is waiting),

P2 goes about its business and issues a bcache_write operation on block 25.

The buffer cache accepts this new block, and makes a copy of it in the buffer cache.

It begins in the DIRTY state, because it reflects data that has not yet

been written to disk. bcache_write can return immediately, trusting that

the I/O scheduler thread will (eventually) write the block to disk.

P2 then repeats this action on blocks 26 and 27.

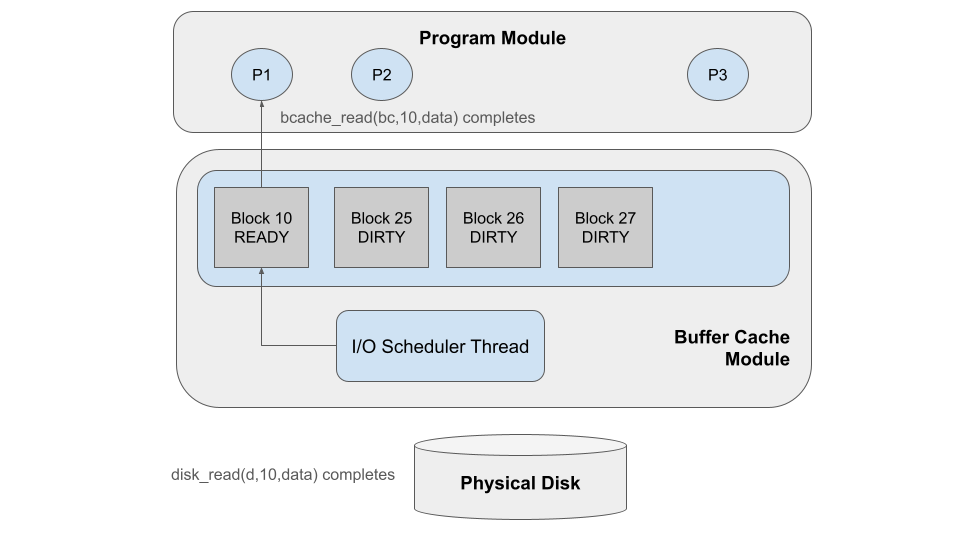

Finally, the I/O scheduler completes the disk_write operation, and marks

block 10 as READY. It notifies the waiting thread that the block is now

ready, and the corresponding bcache_read operation completes, so that P1

can go about its further business.

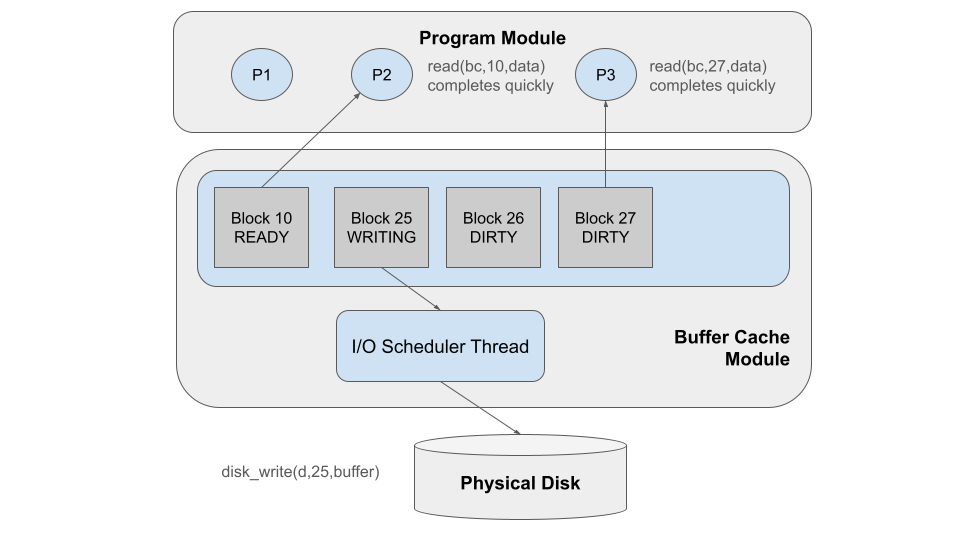

Next, the I/O scheduler looks for more work to do. It notices that Block 25

is dirty, so it changes its state to WRITING and calls disk_write to copy

it back to the disk. In the meantime, P2 calls bcache_read on block 10.

Block 10 is already in the buffer/cache, and so it can be provided to P2 immediately

without waiting for the I/O scheduler thread. In a similar way, P3 calls bcache_read

to read block 27, which is also present and can be provided immediately.

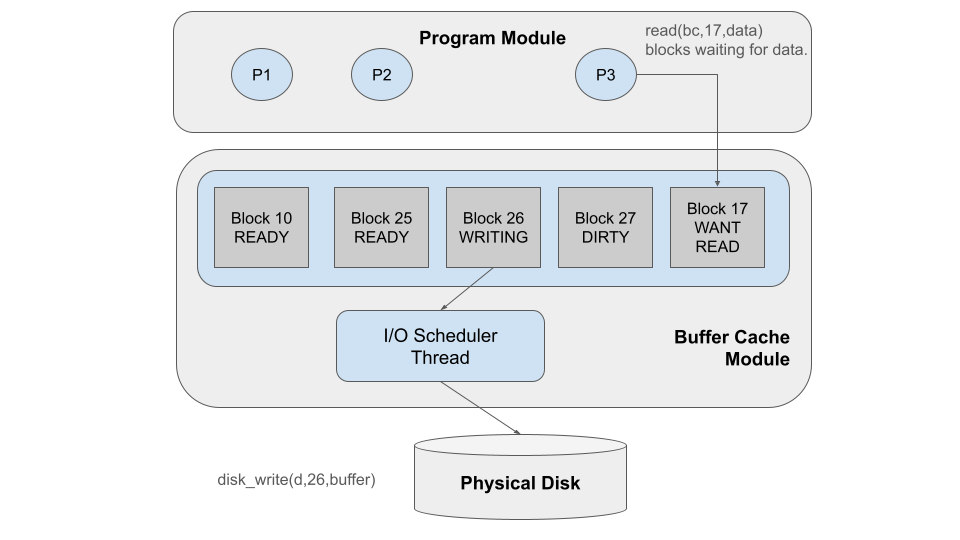

Eventually, the I/O scheduler thread completes working on Block 25,

and marks it as READY, because it is no longer dirty. The scheduler thread

looks for more work to do, and selects block 26. It changes the state to

WRITING and calls disk_write as appropriate. Meanwhile, P3 calls bcache_read

to read block 17, which is not in the cache, and so it blocks in the WANTREAD state.

Things to Figure Out

This project will require that you work out several important details in order to get a correct result. We won’t tell you exactly how to go about it (since there are multiple good solutions) but these are some areas that you will need to ponder.

Data Structures - You can organize the data structure of the buffer cache however you like, as long as it stores the necessary data efficiently. You will probably have a structure representing a single block that looks like this, but you are welcome to add or modify fields as required:

struct block {

int blocknum;

int state;

char data[4096];

};

Thread Synchronization - The programs and the I/O scheduler will run as concurrent threads, all attempting to modify the buffer/cache data structure simultaneously. Use what you have learned about threads and synchronization to make sure that this is done safely, while still permitting independent actions to proceed concurrently.

Replacement Policy - The buffer/cache has a maximum number of blocks it can hold. When the cache becomes full, you must select some block to remove, so that you can allocate space for a new one. Be sure to do so safely, so that you don’t yank away a block in the middle of an access.

Scheduling Policy - The I/O scheduler thread will continually select a new block to act on after completing its current action. Which is the best block to select? Keep in mind that the disk will operate more quickly if it doesn’t have to travel as far between operations.

Corner Cases - Each bcache_read or bcache_write may encounter

a block in any one of the states given above. Take the time to consider

every single state and think through what should happen when a bcache_read

or bcache_write encounters a block in that state.

Getting Started

Download the source code and build it with make.

The system is invoked as follows:

./bcache <nthreads> <buffer-blocks> <disk-blocks>

For example, to run with 5 threads, 10 buffer blocks in memory, and 100 disk blocks:

./bcache 5 10 100

As provided, the system will actually run correctly, although slowly.

We have provided you with a “dummy” implementation of the buffer cache,

in which bcache_read and bcache_write are implemented by calling

disk_read and disk_write directly. The result is that each program

will perform I/O in a blocking manner and run very slowly.

By implementing the buffer cache correctly, you will get this system

to run much faster.

At the end of the run, the main program will print out some key performance metrics, simply counting the number of buffer and disk operations over the elapsed time, like this:

elapsed time: 9.93s

bcache reads: 700

bcache writes: 300

bcache perf: 100.75 ops/s

disk reads: 501

disk writes: 252

disk perf: 75.86 ops/s

Note that the disk will always be less than 100 ops/s, because each operation takes (at least) 10ms. But, by making effective use of the buffer cache, you should be able to get the buffer performance much higher than 100 ops/s. And, by scheduling the I/O thread carefully, you should be able to get the disk performance very close to 100 ops/s.

How fast can you make it go?

Troubleshooting Tips

We suggest that you test your implementation in a variety of configurations of increasing complexity and difficulty, such as:

./bcache 1 100 100 # single thread, memory = disk

./bcache 1 20 100 # single thread, memory < disk

./bcache 10 100 100 # many threads, memory = disk

./bcache 10 20 100 # many threads, memory < disk

./bcache 20 5 100 # many threads, memory < threads

Don’t be surprised if some of these don’t work the first time. If your buffer cache returns an incorrect block back to a program, then you will get a message like this:

CRASH: bcache_read of block %d returned incorrect data from block %d instead!

We recommend that you troubleshoot by adding printfs to indicate

what each thread is doing within bcache_read and bcache_write,

and what the I/O scheduler thread is doing. By tracing through

the set of steps that lead to a crash, you should gain insight

into the nature of the problem.

Turning In

Please review the general instructions for assignments.

This projects is due at 11:59PM on Wednesday April, 30th. Late assignments are not accepted. (And it’s also the end of the semester!)

You should turn the following to one of the partner’s dropboxes:

- All of your source code.

- A

Makefilethat builds the code. - A

PARTNERSfile indicating the names of both partners. - A

RESULTSfile containing the plain text output of the following commands:./bcache 1 100 100 # single thread, memory = disk ./bcache 1 20 100 # single thread, memory < disk ./bcache 10 100 100 # many threads, memory = disk ./bcache 10 20 100 # many threads, memory < disk ./bcache 20 5 100 # many threads, very limited memoryAs a reminder, your dropbox directory is:

/escnfs/courses/sp24-cse-30341.01/dropbox/YOURNAME/project6

Grading

Your grade on this assignment will be based on the following:

- Correct execution with a single program (and one background thread). (50%)

- Correct execution with many programs. (30%)

- Correct execution with many programs and limited memory. (10%)

- Good coding style, including clear formatting, sensible variable names, and useful comments. (10%)