opsys-sp25

CSE 30341 Spring 2025 at Notre Dame

Project 6: Flash Translation

Objectives

Please review the general instructions for assignments.

In this project, you will build a flash translation layer that translates between a conventional block storage device interface and a modern flash storage interface. Through this project, you will:

- understand the unusual properties of flash storage.

- design and implement a translation strategy that is efficient and balanced.

- observe the overheads involved in translating raw storage to usable storage.

- develop even more expertise in C programming with structures and pointers.

This project may be done in pairs or singletons. Please submit your work to a single dropbox with a PARTNERS file that indicates the project members. Both partners will receive the same grade.

This is a challenging project that will take time to get right. Although the total quantity of code is not large (perhaps a two hundred lines or so) you will need to think carefully about designing data structures, dealing with corner cases, measuring performance, and other issues. You will need to think, design, think, code, and think some more. Start the project right away so you have time to get it right.

Overview of Storage Interfaces

A review of what we discussed in class:

A conventional storage device like a hard disk is organized into fixed size disk blocks. typically of 4KB. Each disk block has a distinct numerical address, counting up from zero. The disk provides the ability to read and write entire 4KB disk blocks at once. Each 4KB disk block is an atomic unit: you cannot read or write any less than that. A single disk block can be updated by simply over-writing the existing data.

This abstraction is often called the block storage abstraction and can be represented in C like this:

int disk_read ( struct disk *d, int disk_block, char *data );

int disk_write ( struct disk *d, int disk_block, const char *data );

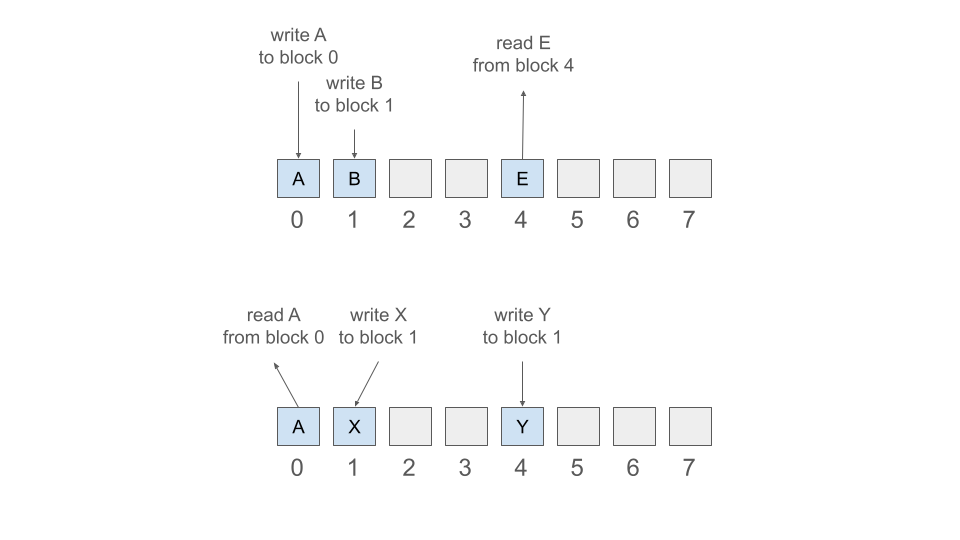

For example, here is an abstract view of a disk with eight blocks. The OS writes A to block 0, then writes B to block 1, and then reads block E. A little later, the OS writes X to page 1 and Y to page 4, over-writing the values that were there before. This sort of overwriting happens frequently in the course of implementing a filesystem.

However, flash storage devices have a different underlying physical structure. A flash drive is organized into flash pages of 4KB each. Pages are then grouped into flash blocks of multiple pages (typically 32-128). Similar to a disk, you can read or write a 4KB flash page atomically. Each flash page is initially “empty” and becomes “full” when written. But, you cannot simply over-write an existing flash page with new data. Instead, it is necessary to “erase” an entire flash block at one time, resetting all the pages in that block back to the “empty” state.

Let’s call this the flash storage abstraction and it can be represented in C like this:

int flash_read ( struct flash_drive *f, int flash_page, char *data );

int flash_write ( struct flash_drive *f, int flash_page, const char *data );

int flash_erase ( struct flash_drive *f, int flash_block );

Note on terms: For some reason, flash device makers have decided to use the terms page and block in a way that is not consistent with the rest of the operating system. So a disk block is the same size as a flash page. If you think that’s confusing, well, I agree, but unfortunately, that’s what they are called. To minimize confusion, this page will clearly indicate disk blocks, flash pages, and flash blocks as needed.

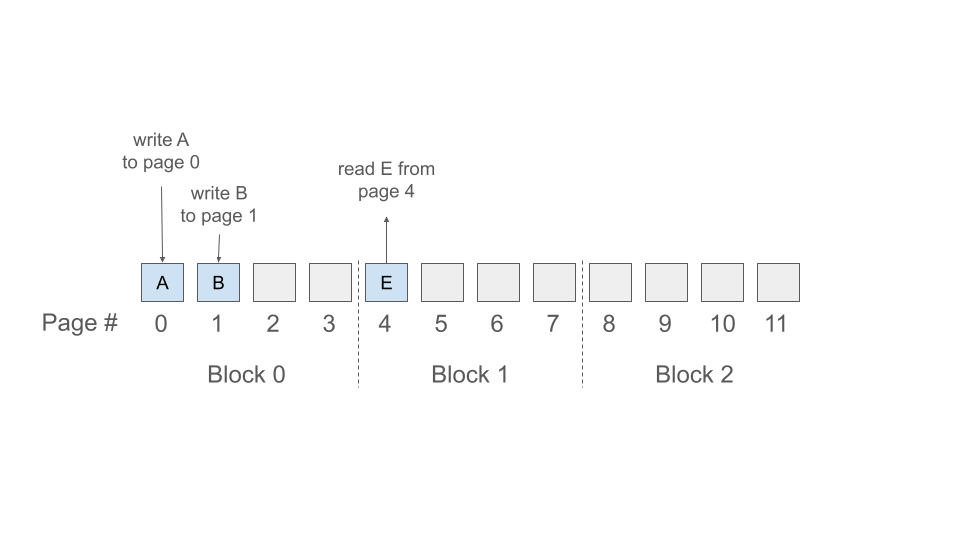

Because of these properties, flash storage devices have to be used in a different way. Here is an example of a flash storage device with 12 flash pages organized into blocks of four pages each. As before, the OS writes A to page 0 and B to page 1, then reads E from page 4. All the same as before.

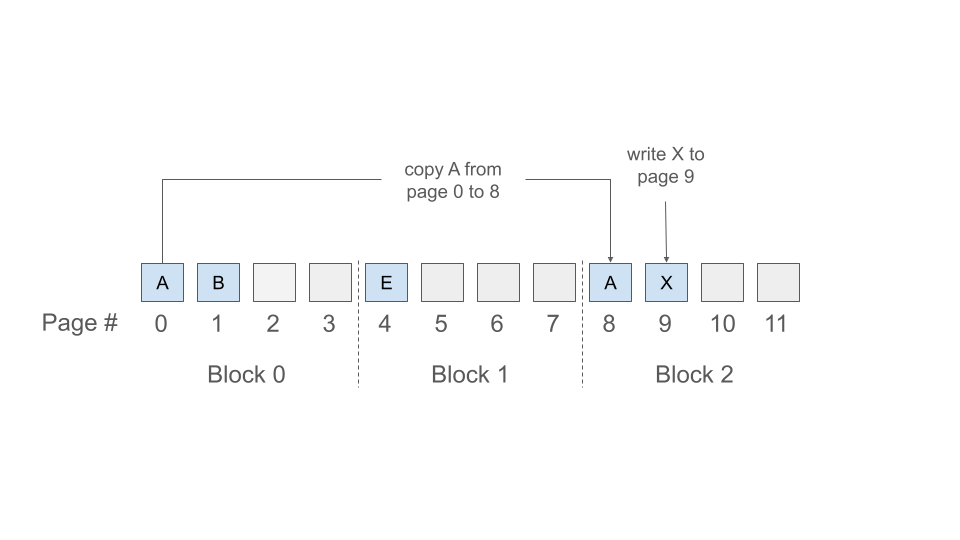

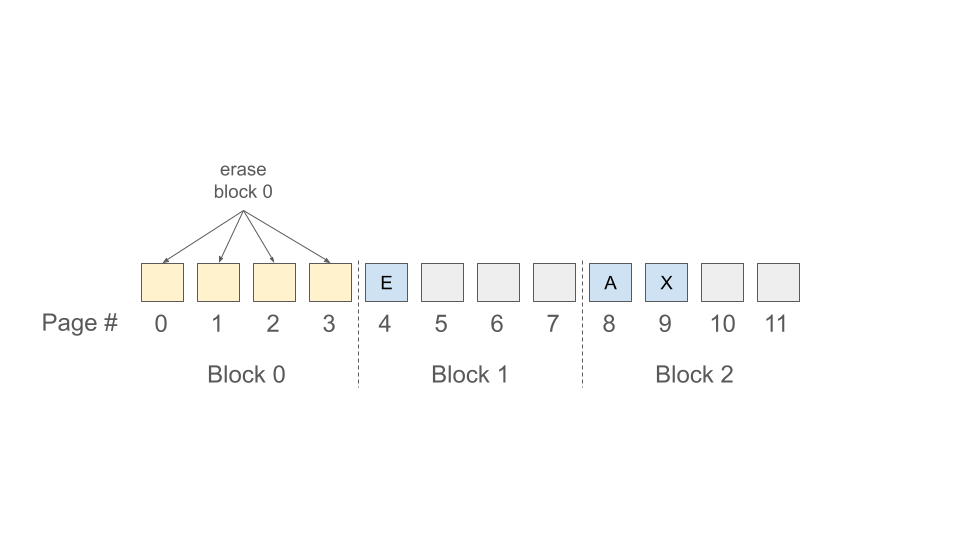

But now, suppose that that OS wants to replace B with X. The device is not capable of simply over-writing that flash page! Instead, it is necessary to rearrange the data into some other available space. Instead, we must copy page 0 to page 8, write the new value B page 9, and then erase block zero, like this:

Flash drives have some nice performance advantages over disk drives. This datasheet describes a typical NAND flash chip: reading a page takes 25us, writing a page takes 300us, but erasing a block takes 2ms. So, best case random access reads are quite fast, but an operation that requires erasing a block and write multiple pages could be as slow as the equivalent write on a hard disk drive.

Another limitation of flash drives is that each page can only be written and erased so many times before it wears out and starts returning invalid data. This is known as the endurance limit, and is typically on the order of 100,000 write-erase cycles. To maximize the lifetime of the device, the operating system must take care to spread writes across the device, and not continually modify the same blocks over and over again. This is called wear levelling.

The Flash Translation Layer

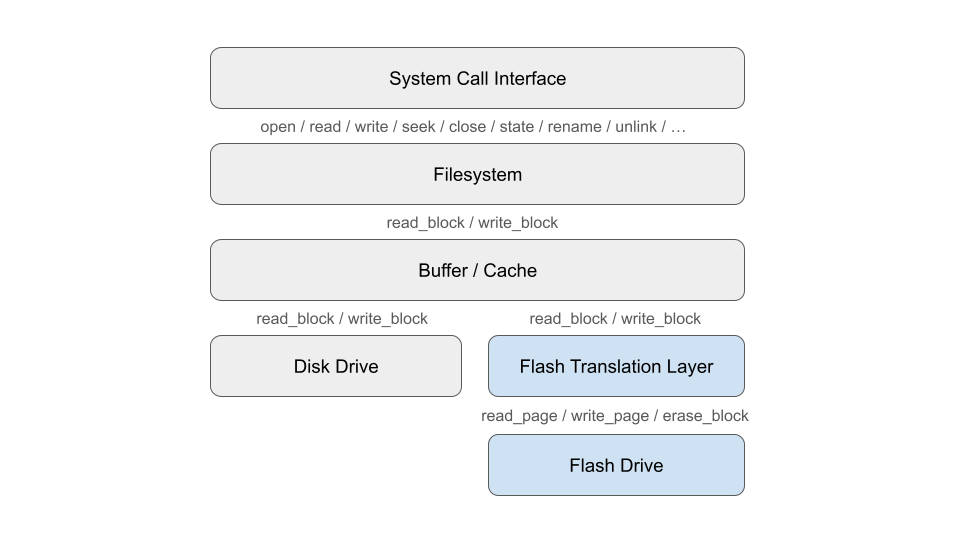

The overall organization of storage in the operating system looks like this:

Applications access files through the system call interface. The filesystem layer transforms those system calls into operations on individual blocks. Frequently used blocks are maintained in the buffer cache. When using a conventional disk, the buffer cache performs block reads and writes on the disk, overwriting blocks as needed.

But, if we introduce a flash device in In order to make flash devices “fit” into the hierarchy, the OS must have a flash translation layer that transforms the block storage abstraction into the flash storage abstraction. It will provide the illusion of a storage device that can be easily overwritten by copying, moving, and remembering where data is stored.

Here is the basic idea: From the outside, the user of the flash translation layer can invoke arbitrary reads and writes on a fixed number of disk blocks. For each read and write, the flash translation layer will direct the operation to a specific flash page. And if necessary, it will copy and rearrange blocks and remember their locations.

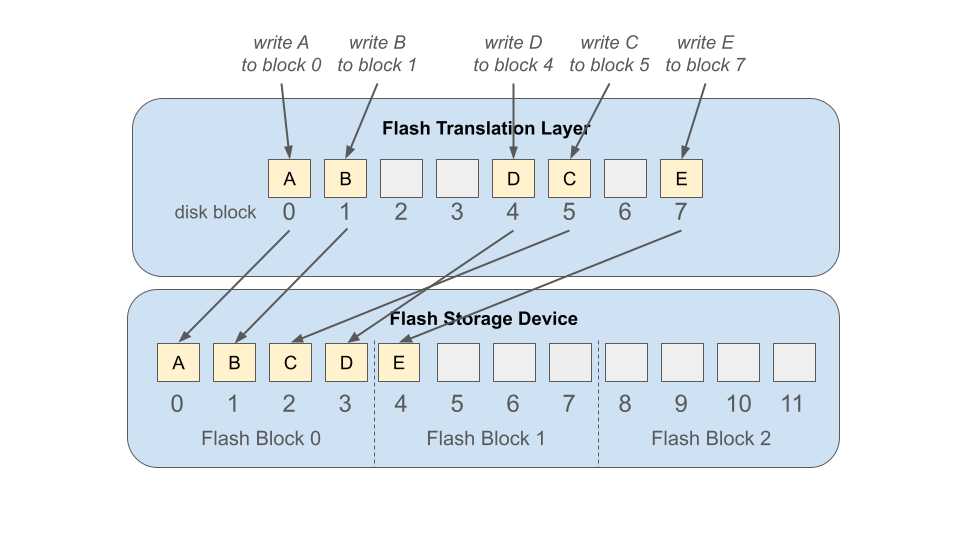

For example, suppose that the OS wants to write disk blocks 0, 1, 5, 4, and 7, in that order. The flash translation layer can choose to put those blocks anywhere. Let’s suppose that it deposits them in flash pages 0 through 4. Here is what that looks like:

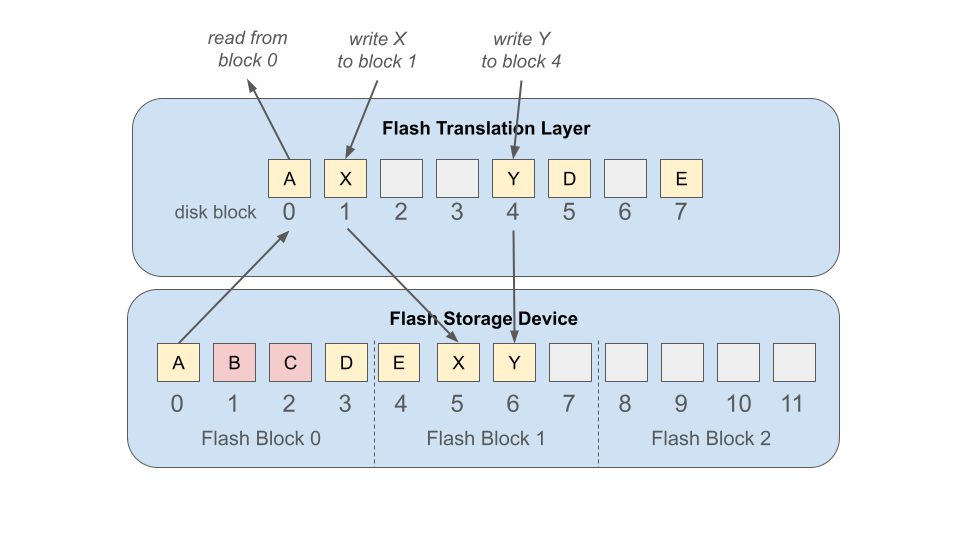

Now, if the OS wants to read back disk block 0, then the flash translation just needs to remember that it is located in page 0, and return that data (A). However, if the OS wishes to write disk blocks 1 and 4, then the translation layer must find new locations for those pages. Here, it chooses to write them to flash pages 5 and 6:

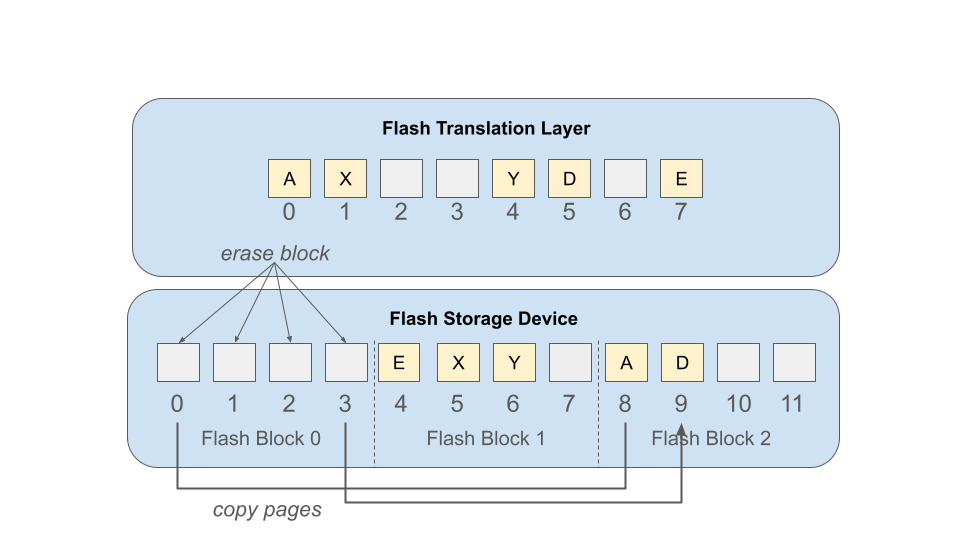

Now, notice something – flash pages 1 and 2 still have their old values, but are no longer needed. We call these “stale” pages. We don’t have to do anything about them immediately, but over time, stale pages will accumulate. To get rid of them, the translation layer needs to clean a flash block by copying all of the live data into a new flash block, and erasing the old block. This eliminates the stale pages, and makes more room for new ones to be written.

Getting Started

Your job is to write a working flash translation layer for a simulated flash disk. To get started, download the source code and build it with make.

The code consists of three components:

main.cis the main program, which generates random read and write requests. (you can read this, but don’t modify)disk.cis the flash translation layer which maps the disk interface to the flash device. (do your work here)flash.cis the simulated flash drive, which can perform read, write, and erase operations. (you can read this, but don’t modify)

The system is invoked as follows:

./flashsim <disk-blocks> <flash-pages> <pages-per-block>

For example, to run with 64 disk blocks and 128 flash pages in blocks of 8 pages:

./flashsim 64 128 8

As provided, the system will start to run, but won’t operate correctly. For each disk block read or written, the (starter) translation layer will simply access the flash page with the same number. This will probably work for a few requests, but at some point, the system will attempt to over-write an existing block, and the flash disk will abort with an error:

ERROR: flash_write: attempt to over-write page 17 without erasing first!

If the run is successful, then the main program will print out some key performance metrics, counting the number of disk and flash operations as well as the relative wear load on the flash pages:

System Performance:

disk reads: 7979

disk writes: 2085

flash reads: 14027

flash writes: 8133

flash erases: 1008

wear differential:

most written: page 8 was written 109 times

least written: page 56 was written 86 times

ratio of most/least: 1.27

Note that, in real hardware, the number of flash-pages-per-block is fixed by the hardware and cannot be changed. But since we are making a simulation, we can vary that design parameter at runtime with each run, in order to observe its effect.

Things to Figure Out

This project will require that you work out several important details in order to get a correct, working system. We won’t tell you exactly how to go about it (since there are multiple good solutions) but these are some areas that you will need to ponder.

Data Structures - You can organize the data structure of the translation layer however you like, as long as it stores the necessary data efficiently. Consider how you will track the mapping of disk blocks to flash pages, the state of each flash page, and the condition of each flash block.

Cleaning Policy - Consider how and when you will clean a flash block, so that it can be used for new writes. Should you aggressively clean whenever one page in a block changes? Should you wait until the entire block is dirty? Are there any other considerations?

Wear Leveling - The flash disk will wear out if any one block is erased much more frequently than the others. What strategy can you use to ensure that the same block doesn’t get picked over and over again?

Corner Cases - Each disk_read or disk_write may encounter

a block in any one of the states given above. Take the time to consider

every single state and think through what should happen when a disk_read

or disk_write encounters a block in that state.

Troubleshooting Tips

We suggest that you test you begin by testing your implementation with some small examples where you can easily trace exactly what is happening:

./flashsim 8 16 4 # 8 disk blocks, 16 flash pages, 4 pages per block

Then, once you have gained confidence that you have a correct result, try some larger configurations:

./flashsim 128 256 16

Don’t be surprised if some of these don’t work the first time. If your buffer cache returns an incorrect block back to a program, then you will get a message like this:

CRASH: disk_read of block %d returned incorrect data!

We recommend that you troubleshoot by adding printfs to indicate

what each disk_read and disk_write are doing, what the state

of each page is, and so forth. By carefully tracing through

the set of steps that lead to a crash, you should gain insight

into the nature of the problem.

Lab Report

Finally, write a lab report to describe the overall behavior of the system that you have designed.

First, describe how your system works:

- Describe how you designed the data structures for keeping track of everything. Walk through some simple examples of reads and writes to explain how they work.

- Describe your policy for selecting which page to write. Are there any tradeoffs in selecting this policy?

- Describe your policy for when and how to clean blocks. Again, are there any tradeoffs?

- Describe your policy for wear leveling. Again, are there any tradeoffs?

Then, present the overall performance of your system:

- Starting with a configuration of

8 16 4, double the number of disk-blocks (and flash-pages) while holding the pages-per-block constant, up to256 512 4. Produce a plot that shows how each of the measured values (disk reads/writes, flash reads/writes/erases) varies with the configuration. Explain any trends that you observe in the results. - Starting with a configuration of

128 256 4, double the pages-per-block until the system stops working. In a similar way, plot the measured values, and explain any trends. - Starting with a configuration of

128 256 16, reduce the number of flash pages until the system stops working. In a similar way, plot the measured values, and explain any trends.

There is no specific length requirement. I am more interested in your words than in fonts/margins/formatting, etc, so keep it simple. Write out your responses carefully, clearly, and thoughtfully. Prepare your plots carefully so that everything is appropriately labelled and easily readable. Don’t add fluff just to make it longer.

Turning In

Please review the general instructions for assignments.

This projects is due at 11:59PM on Wednesday April, 30th Friday, May 2nd. Late assignments are not accepted. (And it’s also the end of the semester!)

You should turn the following to one of the partner’s dropboxes:

- All of your

.cand.hfiles. - A

Makefilethat builds the code. - A

PARTNERSfile indicating the login names of both partners. - A file

labreport.pdfthat contains the answers and discussions indicated above.

As a reminder, your dropbox directory is:

/escnfs/courses/sp25-cse-30341.01/dropbox/YOURNAME/project6

Grading

Your grade on this assignment will be based on the following:

- Correct execution of the flash translation layer code. (60%)

- Discussion of the overall system design and tradeoffs. (15%)

- Performance evaluation and discussion of observations. (15%)

- Good coding style, including clear formatting, sensible variable names, and useful comments. (10%)